Please join me on Substack at https://karensandstrom.substack.com/. Thanks for reading!

DON'T POUR TEA FOR THE WEASEL

Since this is an embarrassing public service announcement about falling prey to something akin to a scam, I'd like to frontload it with a few established facts.

First: I am the designated skeptic in our house, the one most likely to not answer the door if a stranger comes knocking.

Second, I take disproportionate pride in passing all the phishing-test emails the IT department sends out at work.

Third, about 10 days before this incident took place, I aced an online quiz titled "Could You Be the Victim of a Scam?" I like to think I have a Grade A bullshit detector bestowed via the miracle of genetics and 25 years as a journalist.

But now I don't know.

It's late afternoon on a workday and the dog starts barking her frantic someone's-at-the-door bark. I look out the window to see a young woman wearing a reflective vest — like something a utility worker would wear — so I decide I'd better see what's up. I step onto the porch, where she holds up a letter from Dominion, our natural gas supplier, and says she's being sent to follow up with folks who didn't answer the letter. There's a vague sense of emergency in her voice, and it's true that I ignore almost every piece of mail from Dominion because I pay my bill online. So instead of telling her to take a hike, I listen more.

Right here I'm going to say that it's about 5 in the afternoon, when I am at neither my sharpest nor most caffeinated.

At any rate, It takes a few minutes for me to realize she is not actually FROM Dominion, but from another company that supplies natural gas via Dominion gas lines. But I actually did have to say, "Oh, so you're not from Dominion, then?" before she admitted that she was not.

Instead, she spins a tale about how Dominion could raise my natural gas rates up to $12 per cubic whatever, and asks me if I know what I'm paying now, and of course I don't, so I agree to look up my bill online to see that I'm currently paying about $4. Her sell is that if I sign with her company (what was the name again?) I could lock in a guarantee of $6 per cubic whatever for a year.

It wasn't as if my skeptical self sauntered back into the house to do some day drinking. No, she was saying, "Hmm. Six dollars is more than four. Does that make any sense to you, Karen?"

But I was vaguely aware of news stories predicting spikes in natural gas prices due to Russia's ongoing rape of Ukraine as well as climate change weather events that have made this summer, we'd have to agree, a season of Biblical cataclysmic heat, fires and floods that suggests we actually have crossed the Rubicon and now the scientists are just too kind to mention it anymore.

But I digress. What was happening on the porch with Reflective Vest Lady is that I was feeling a little guilty for never having checked into alternate natural gas suppliers, so I kept listening. Also — and this is important — now that I had answered the door, I didn't want to be the person who wouldn't listen. Plus, she was sort of charming.

Inside, of course, my skeptic was whispering, "You should not be engaging with this person; it's not too late to send her on her way," but my journalist part was responding with, "And I will, if I detect that this is a scam. And I will know if it's a scam, because I pass all those phishing tests at work."

By the way, it isn't precisely a scam. I ask enough questions to satisfy myself that this is a real company that delivers an actual product, although skeptical Karen isn't sure about agreeing to something that costs more than I am currently paying. Still: Ukraine. Floods. Fires. Price hikes.

Long story short, I agree to switch.

This entails giving a stranger my Dominion account number — a fact which gives me a five-alarm shame attack to admit, but I did it. Why WOULDN'T I have to do that, after all? I was authorizing this company (what was its name again?) to tell Dominion I am switching my natural gas provider.

Along the way, Reflective Vest Lady makes conversation. Did I have any tattoos? She and her mom were going to go together to get tattoos. What kind of dog is Daisy?

When the time draws near to sign the contract, there is one more step, which involves a third party verification company calling me on my cell phone to answer some brief questions. Reflective Vest hits some keys on her iPad, triggering a call to my cell phone, where the representative explains that her job is to determine whether I know what I am getting myself into (ha!) and that she will be asking me a series of questions which I am to answer very straightforwardly yes or no.

Her first question is whether I can confirm that the salesperson has left my property. But of course she is still sitting on our glider on the front porch. So, stumped, I hold my phone against my chest and tell Reflective Vest what I am being asked, and she whispers, "That's OK, just say yes."

I get back on the phone, and the verifier lady is saying, "Who were you talking to? It sounds like the salesperson is still there. Can you confirm that they have left your property?"

So I hang up on the verifier. "Look," I tell RV, "she was asking whether you are still here. I assume that's because she wanted to be sure you were gone as I answered the survey."

RV starts explaining why the company asks that and why it shouldn't matter, but the more she talks, the more the explanation sounds like it was written by Trump at 3 in the morning.

"I don't care," I tell her. "I'm not going to lie for this."

Don't I sound like a smart, reasonable person here?

Now, I see this little flash of anger in RV's eyes, almost as if she has forgotten the nice mother-daughter tattoo outing in her near future. And she says, with a frisson of passive aggression, "Fine. I'll leave, and I can have them call you back again."

That seems reasonable. So I answer a few more of RV's questions reiterating the terms of the contract and agreeing to switch providers. Then she triggers the verification process again and leaves my porch, and I go inside and answer the verifier's questions, including the ones that acknowledge that I can cancel the contract at no charge within 30 days, and after that I would be charged $150 to cancel. And that if I wanted to cancel, I had to call my local utility company (Dominion) to inform them.

Done deal.

Then I get off the phone and check my email where, as I had been promised, I find a communication with the contract attached. And of course the company's name (what was it again?) is on the letterhead, so I do the smart thing and look them up on the Better Business Bureau site.

And there I find a litany of complaints so egregious that my laptop practically bursts into flames.

In the words of Bugs Bunny, what a maroon.

To add insult to injury, at that very moment our neighborhood's Facebook page is lit up with warning posts about this shady-seeming young woman who is going door-to-door in a reflective vest.

I immediately call Dominion, where a representative answers the phone with "How can I help you?"

I tell her, "Well, I, um ... think I was scammed and I feel like a jerk."

"Uh-huh. People going door-to-door?" she asks.

Then she very kindly describes the basics of the interaction I'd just had, tells me it's not my fault, and makes a point that these companies especially prey on places where older people and people who are not that tech-savvy tend to live. I tell her I didn't consider myself to be in either category, but that doesn't stop her from repeating that little detail again later in the otherwise pleasant 10-minute conversation where we iron things out.

Bottom line: The Dominion lady put a note in my account file indicating that we do not want to change natural gas providers. She also tells me to call the company and cancel the contract, and to be prepared to be harsh, since these companies often get nasty when folks try to cancel. She gives me the number for the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio, and suggests I tell the company that I am willing to call and report them to PUCO if they give me any grief.

"And I'm sorry to tell you this," she adds, "but since these people now have your information, sometimes what they do is wait a bit, then resubmit it to us as if you have authorized the switch. They won't tell you they've done it. So you really need to call us back about once a week for several months until they get tired and move onto someone else."

SEVERAL MONTHS.

The next day, I called the company and canceled. It all seemed to go very smoothly and easily, which of course made me super-suspicious, because after all I had seen the BBB complaints about how much they lie. And now I have a reminder on my calendar to call Dominion every Thursday to confirm that they are still my natural gas supplier.

As Wordle says when you bat a six, "Phew."

I spent about a day feeling extremely ashamed of myself, wondering how a woman can turn into the I've-Fallen-And-I-Can't-Get-Up person in the span of an hour.

But the Dominion rep had said one thing that I think is worth noting.

These people are very good at what they do.

For every person they sign to a new contract, the salesfolk earn $100. My guess is that they knock on a lot of doors before they hit that $100, and also that they have been trained in techniques that exploit any little cracks in the foundation.

In my case, those vulnerabilities were low late-day power reserves, guilt about not having previously investigated alternative gas suppliers, my belief that I was too smart to be had, and then of course the problem of looking at someone on my porch and telling them to leave. I was raised to be a nice girl, and no amount of journalism training ever washes that scourge away completely.

So I offer this embarrassment of a story because scammers — and real companies that use scammer sales techniques — really grind my gears and I want to interrupt their mojo.

Over the last few years, scammers have gone after two of my smartest friends. One scammer succeeded and the other was a near miss. I was hoping my friends might share their stories widely, but I understand why they didn't. In a closed-group online community I'm part of, a friend admitted that she had been scammed and that it deeply devastated her sense of herself. The part of me that spent a day self-flagellating with colorful, Karen-directed profanity gets that completely.

The day after all this happened, I hopped on Amazon to order a "no soliciting" sign for our front door. I remembered seeing these things once when I canvassed for a school levy. I figured the person behind the door was about 102 and had some quaint beliefs that a sign like that might really keep unwanted visitors away.

I know it won't. But I put the sign up anyway -- for me. Now, whenever I open my front door, there it is, a shiny reminder to myself that the weasels are out there. They will call on the phone. They will knock on the door. They will be charming. Some will be convincing.

My job is to remember not to invite them in for tea.

WHAT THE RABBIT THOUGHT

In the night, when it's just the moon and me,

and some reassuring fireflies,

I remember that you are there always.

Always like the moon,

always like the sun and the roots of century trees,

when I can see you and when I can't,

steady and steadfast,

always and always.

The moon and the fireflies remind me.

They do their best to calm my rabbit heart.

TAKING CARE OF THE BEAR

Let's say you have a nice house with a deck. The floor is elevated a few feet, and a wooden lattice around the base prevents skunks from hiding underneath and stinking up the place. One day you notice the lattice has been ripped away, and a bear is slumbering under your deck. This problem strikes you as so large and imposing that, instead of making it your business to get the bear out of there no matter what it takes, you simply reject the information and hope the bear goes away.

The bear settles in. By night, she wanders the neighborhood searching for food. In the morning, your new friend is back there snoring, and scattered around the deck is evidence of bear bacchanalia: a KFC bucket, beer cans and seven scavenged dog toys. Now you have a bear under the deck plus an eyesore.

The neighbors start whispering. So you do the natural thing: While the bear sleeps, you nail sheets of wood around the base of the deck to hide the bear and her mess. You stain the wood so it looks nice and leave an opening in hopes that the bear will leave and solve your problem. Instead, you've just given her more privacy — made her more comfortable. And the longer she stays, the sloppier she gets until one day you find that you're spending a lot of time picking up bear garbage in your yard and hoping the neighbors don't file a complaint.

This image ran through my head the other day as I was thinking specifically about the problems some of us (many of us?) have had in our dysregulated relationships with food. When I was growing up in the 60s and 70s, there was a single standard of beauty to which white American women were held. It had various names — Twiggy, Christie, Cheryl — but it was always tall, blond and Virginia-Slims-thin. It was a rough environment for almost anyone who didn't have a preternatural ability to reject standards set out by the media and reinforced by one's peers.

For the longest time, I fantasized that our culture would magically shift its ideas of female beauty back to the Renaissance, where thick thighs and zaftig juiciness were enviable features. Or at least acceptable. Or at least not UNACCEPTED. Or at the VERY least, not mistaken for lack of character and stupidity.

That was not the world of the 70s.

Or 80s.

Or 90s.

So those of us with Food Issues became ambidextrous. In one hand we held the whip of self-flagellation. In the other, a cupcake.

Today, our culture still prizes female beauty, but the tyranny of tall-thin-and-blonde has given way to much more democratic ideas of what can constitute physical acceptability and beauty. Today we have Lizzo. We can be large and in charge. We can own our big butts and round bellies. The practice of body shaming will never completely go away, but younger generations have correctly reframed it as just another unseemly form of prejudice. On social media, body shamers find themselves huddling outside under an awning in the rain, like the last people in the office who still smoke.

In other words, my fantasy has, in part, come true. I am an average woman living in a world that prevailingly no longer gives a shit about "thunder thighs." (Young people: Have you even heard that phrase?) I have no doubt that being fat is still a barrier to entry in some worlds; my husband and I have been streaming the law-firm drama "Suits," and I suspect that real life white shoe firms still prefer their female partners to be couture-slender, as they are on the series. But in general, social acceptance seems far less connected to being thin than it was in decades past.

And yet.

The truth is that for me, freedom from self-loathing around my body is only possible when I am facing my food-addicted brain and managing well. Self-judgment that used to be tied to what others think about how I look is instead tied to whether I'm handling the kitchen — and the space between my ears — in a way that aligns with reasonable eating and a reasonable-for-me weight.

On a given day, if I'm mainlining scone batter, I feel like Jaba the Hutt, regardless of what I weigh. But if I successfully face down the food demons, I feel like I look great, even if I weight more than the BMI charts say I should. Even if I actually look like a late-middle-aged woman with thinning, graying hair and aging Irish skin and a sagging chin and Fred Flintstone feet. When I'm eating healthy meals and rejecting junk, I feel like one of those unreasonably handsome older women in a Prevagen commercial.

Both images are illusions, but I prefer the second. Feeling good in one's skin is what comes from treating oneself well for the sake of treating oneself well.

Everyone has their own requirement for what it takes to feel good. The requirement is less a decision, I think, than something that has been programmed into us. The issue isn't thin versus fat; it's peace versus chaos.

For me, peace requires that I get up each day and evict the bear. It doesn't matter what the neighbors think. It never did. The problem has always been that there's a bear dragging trash under my deck, and the household cannot be right as long as I ignore her. She'll keep coming back. I hope one day she'll get bored and show up less frequently, but there's no telling.

In the meantime, I get up, look her straight in the eye and tell her to scram.

A SEASON OF NON-STRIVING

Nectar feeders hang outside the screened porch at my sister-in-law's house in Ann Arbor. On a sunny day, you can sip a drink and watch lots of ruby-throated hummingbirds zip in to refuel, then buzz away to perch in a massive evergreen across the driveway. One name for a flock of hummingbirds is a "bouquet." Here you can see a bouquet of hummingbirds all summer long from the comfort of a wicker chair.

At my house, if you happen by a certain window at the right, random moment in early morning or before dusk, you have one chance in 500 of catching a glimpse of a lone female taking a quick drink at my feeder. If she sees you watching her, she's gone. You can stare at the feeder until you start thinking that the nectar is actually evaporating right through the glass, but no matter. That bird will not be back while you're watching.

Over the decades that I've been trying to attract hummingbirds to my yard, they have mostly not shown up at all. Occasionally, one teases me with a brief visit. Once in late summer, well after I'd given up and put away the feeder, a hummingbird visited for a few days, trying to draw nectar from bulbs on some Christmas lights I hadn't bothered taking down. I put the feeder up again. That was the bird's cue to leave.

I've thrown away gallons of unconsumed nectar, tried various feeder designs, placed them in different locations. Did the nectar go bad? I'd dump it and refill. Did I mix it wrong? I'd buy the pre-mixed stuff. One year I planted bee balm — a supposedly sure-fire approach. The bee balm was dead by Labor Day, and no hummingbirds ever appeared. It was hard not to take it personally.

The amount of wheel-spinning, hand-wringing and fruitless striving I've done in the hope of luring a hummingbird for the season surprises even me, although it should not.

When I was a teenager, all I wanted was a boyfriend. The harder I wanted one, the more elusive he was. The more elusive he was, the harder I thought about how to crack the code. How could I fix myself? How could I become a girlfriend-type girl? I burned a lot of calories obsessing about my deficits, and trying to remedy them; Glamour magazine was a lot less useful in this effort than you might think.

It all just made me hungry.

Eventually, grace — not strategy, fretting or wheel-spinning — delivered me a boyfriend. But it did not deliver me from striving, and I suspect I have a lot of company. We humans are a strive-ish tribe, aren't we?

Writer Arthur C. Brooks addresses this obliquely in "Strength to Strength: Finding Success, Happiness and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life." The book is written mostly for extreme A-listers of every industry whose focus on achievements can become problematic later in life. It is inevitable that we lose professional relevance as we age, Brooks writes. But we can learn to gracefully cede the spotlight to new generations and find different, more rewarding ways to measure our worth.

Despite its orientation toward top achievers, the book has something to offer the rest of us mere mortals as well. This includes anyone who suspects the phrase "middle-age" no longer describes them as accurately as it used to. It also applies to those of us who wish we'd accomplished more, left an indelible mark or been recognized as, in some way, special. ("Special," as Brooks points out, doesn't have nearly the shelf life we think it has.)

What struck me after reading "Strength to Strength" was that I'd spent my entire adult life hoping to achieve one thing or another, occasionally striking gold and sometimes striking out. The wanting-and-striving cycle became a habit it had never occurred to me to quit. Long past what Don Lemon would consider my "peak" years, I continued to want and wish and covet and strive with the best of them.

I am tired of such struggle.

What would it be like to stop? I have started to wonder this. I am not interested in checking out, or ceasing meaningful endeavors, but I think it's time to quit breathlessly chasing some worthier version of myself so as to attract the brass ring du jour. Over the decades, I have strived for social clout, acclaim, thinness, coveted jobs or projects, big love, the approval of my heroes, and yes — "specialness." I've read Wayne Dyer from the "Your Erroneous Zones" days to his late mystical stuff, all in hopes of winning gifts from the universe.

I could go on. Maybe you could, too. But must we?

At a certain age — let's say 62, for the sake of argument — one can't help noticing that there's a difference between grasping for what we covet and investing in the stuff with real value: people we love, communities we share, and meaningful work or service. Chasing has such a low return on investment, if you ask me.

Life has a way of delivering the goods when we're not oozing desperation. Make fun of Kenny Loggins all you want, but he wrote a whole song about this phenomenon in 1978 called "Wait a Little While," and it is perfect.

More to the point, though, there comes a season for learning to detach a bit from the goods themselves. Less hoping to have what we want, and more wanting what we have, as the saying goes.

Back on my deck, I haven't seen my hummingbird in about four days. I plan to keep the feeder filled with nectar all summer just the same. If the bird shows up again, I'll get my hummingbird fix. If she doesn't, I'll get to watch my aging, lucky, unremarkable, semi-special self learning to let the world spin.

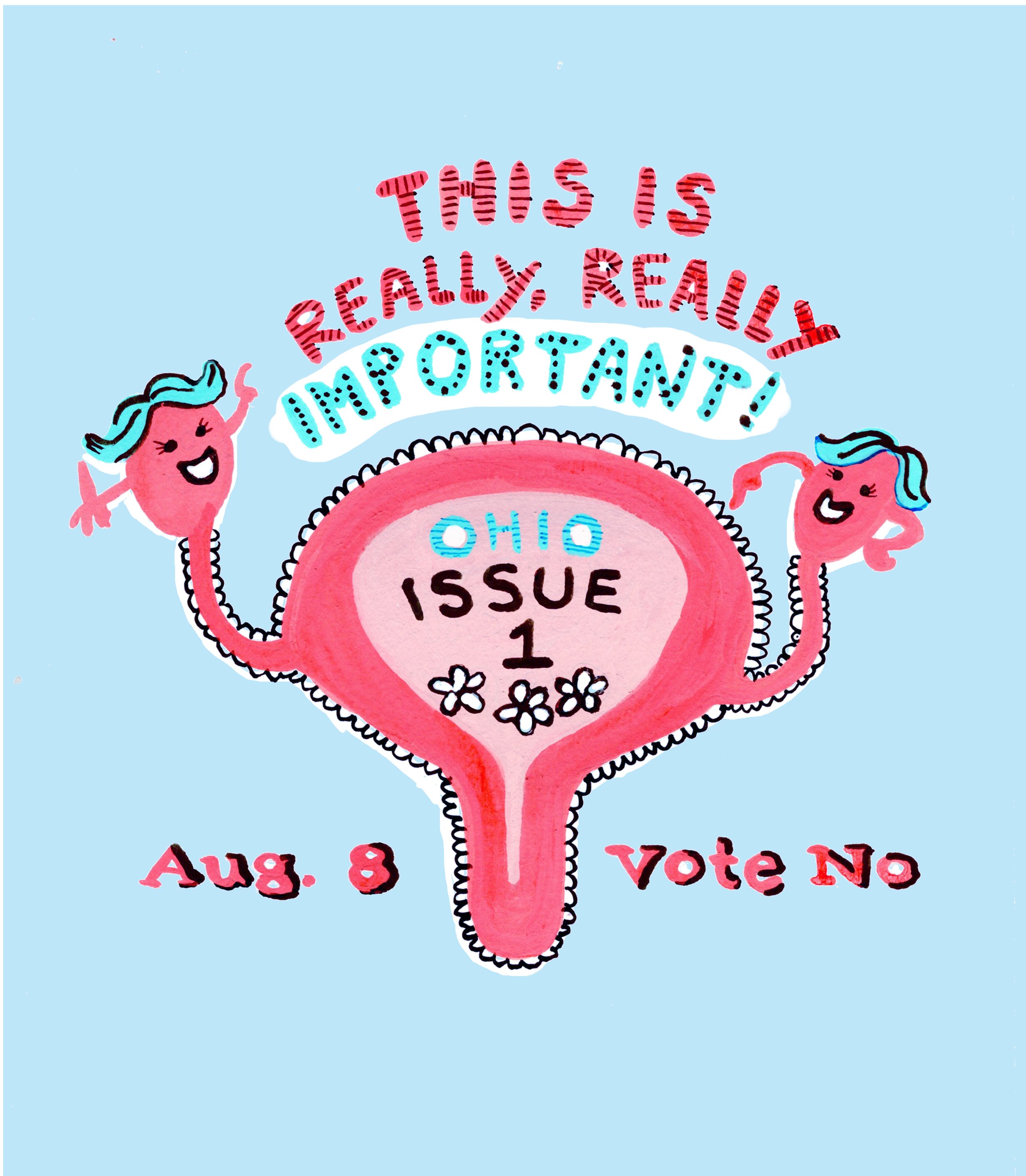

Ohio Issue 1: A Letter From My Shriveled Ovaries

Welcome, and thank you for your attention.

I will be brief.

I write today on behalf of my shriveled ovaries, who, despite the fact that their work here on Earth is done, are compelled to speak out — especially but not ONLY — on behalf of current and future fertile women and those who love them.

Together, my ovaries and I want to urge every Ohio citizen to put two actions at the tippy top of their summer to-do list:

1. Get a big red Sharpie today and mark "VOTE NO" on your calendar for August 8. Do this on every calendar you use. Even your Outlook calendar at work. With a Sharpie.

2. On August 8, actually go to the polls and VOTE NO ON ISSUE 1.

Do it. Find your polling place and vote. Even though this is not a presidential election. Even though it's summer, and what you need is more R&R, not another obligation.

Even though you are entertaining visitors from out of state.

Or have a job interview.

Or your allergies are killing you.

Even from their privileged position of retirement, my ovaries understand that you live a complicated life that includes many challenges and that you do not need one more task, thank you very much. Plus, a person can wake up on Election Day and feel suddenly repelled by bad weather and ennui.

Will one vote really matter? This election, the answer is YES. It will.

Definitely.

Especially.

Urgently.

Indubitably.

Issue 1 is not just another school levy or council race. It's almost impossible to overstate its importance to your democratic rights — even if you are an Independent! Or a Republican!

It matters a lot, regardless of whether your ovaries are dried up and done for like mine; ripe and dreaming of making future humans; have been surgically removed; or are, in fact, actually testicles.

Issue 1 is a proposal by Ohio Republican lawmakers to MAKE IT HARDER FOR VOTERS to change the state constitution. And they want to do this because in November, voters will again be asked to go to the polls, this time to decide whether to amend the state constitution to protect abortion rights. (Spoiler: State legislators, of whom only 30 percent are female, want to outlaw abortion in Ohio.)

But even if you don't want to ban abortion in Ohio, you should vote NO ON ISSUE 1 ON AUGUST 8, and here's why.

Issue 1 would do three things:

It requires that proposed amendments to the constitution earn 60% of the votes instead of the current 50% plus one vote. (That is likely the difference between the amendment passing or failing.)

It requires that in order to place a referendum on the ballot, signatures be gathered from 5% of the eligible voters in all 88 counties rather than just from 44 counties, as it is now.

It prevents additional signatures from being added to an amendment petition after it has been filed with the Secretary of State. In other words, if the state rejects and disqualifies some of the petition signatures, proponents can't go gather more to cover the gap.

To be honest, my ovaries are VERY angry about this. I've never seen them so mad.

All of these measures leech away power from you as an individual voter and hand it back to state lawmakers, who might or might not actually represent your interests.

Many systems are currently in place in our country that contradict the one-person/one-vote ideal, including the godforsaken Electoral College, although my ovaries begged me not to mention that.

Never mind then.

The point is that a ballot initiative to amend the constitution is one of the rare times that your one vote gets fully counted. Issue 1, if passed, would radically change that.

So, sure: This year, the amendment in question might be abortion, to which you may be personally opposed. But next year, an amendment proposal might be on an issue you deeply care about and want to see put to a vote. But by that time, if Issue 1 has been passed, you'll have given power back to the politicians and you won't get it back.

What my shriveled ovaries really want you to know is that a NO ON ISSUE 1 vote on Aug. 8 is essential regardless of whether you are a person who might ever need an abortion. Issue 1 isn't about abortion. It's about your right as an Ohioan to demand that your vote be counted regardless of which party is in power in the state legislature.

If this plea has been persuasive, there is one more item to consider for your summer to-do list: Spread the word. Talk especially to friends and family members who don't vote, or only vote for president. Explain why this election is different, because they're not voting for a politician or a tax or a policy. They are voting for themselves.

Thanks for reading.

Sincerely,

Karen

THE EPIC

At the far eastern end of the Pennsylvania Turnpike, homing in on a New Jersey beach vacation, my iPhone shuffles up the Pat Metheny Group playing "The Epic" from American Garage, as it has done many times before. This time, however, something is different. This time, with the Philadelphia skyline soon to come into view, the song plays and a 37-year cloud cover of grief parts for sunshine.

This is ultimately a happy story, but I have to tell the sad part first, even though I have told it many times before.

I first heard American Garage in 1979, not through any musical adventuring of my own, but because my brother Greg bought the album and played it and played it. As he had done with other bands and songs, he managed to transfer the tunes onto my internal playlist. At just short of 13 minutes, "The Epic" is a jazz fusion instrumental with sections that feel almost like classical movements. Some are, to me, ecstatically beautiful. I have read that Metheny, a guitarist, and collaborator Lyle Mays, a pianist, came to be critical of the song for being "all over the place." I think that's one of the best things about it.

Back to Greg.

In the very early morning of September 11, 1985, he was killed when his friend plowed their car into the back of a semi on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. The roof was sheared off. We'll never know why the accident happened, exactly, but I suspect Greg's friend fell asleep at the wheel. His blood alcohol level was 0.08, still under the legal definition of drunk driving for that time. They'd been at a Sting concert at Blossom Music Center in Ohio and were headed home to Pittsburgh. They almost made it.

His friend spent six months in jail, but was, physically at least, uninjured.

Greg was 28 when he died, the youngest of my three brothers. I was 24, and the only girl. He left behind a lot of friends and ski equipment, the memory of his sense of humor and mischief, and a half-opened bud of a life. It would be inaccurate to say his death broke our family, but each of us did our individual breaking on the inside, in isolation. Sudden, tragic loss violates the soul in a manner most harsh.

I was not adept at metabolizing that much grief. What that looked like on any given day varied, but the most pronounced and constant symptom was my inability to loosen my fixation on the story of how Greg's life ended. I imagined and reimagined the crash, the scene, the sirens and the fatal injuries. In the absence of a particular fact, my brain invented details — more and more of them as time passed. The funeral director had asked my parents for a photograph to confirm Greg's identity, and encouraged them to leave the casket closed. They did. In the weeks and months that followed, I became critical of that decision, because not having seen my brother made his death seem unreal. I thought we could have handled seeing some cuts and bruises if it meant having more of a sense of closure.

Only much later did it dawn on me how devastating his injuries must have been. What they probably were.

"May his memory be a blessing."

I first read these words on Facebook from Jewish friends offering them in condolence to someone who had lost a family member. What a profound message: In a single sentence, it is an act of loving kindness and a salve.

It is also, to my mind, a self-help book. What we make of grief is, in part, up to us, even if it doesn't feel like it in the moment. When our loved ones depart, they leave us with all kinds of memories and feelings, but we get to pick which ones to replay. Some people understand that right away. At the first easing of acute grief, they begin accepting the blessings of good memories. They nourish the best and let the worst blow away like storm clouds.

Others of us get so snagged on the end of the story — the trauma and details and the pain of the death itself — that we effectively negate all the good things our person achieved during his one and epic life, however long it lasted.

The trauma of sudden loss is immense, and I don't want to suggest that we could just "get over it" even if we wanted to. I'm only suggesting that it's OK if what we want is to bring the blessings forward.

So there I am, driving along the Pennsylvania Turnpike — the same highway that swallowed Greg's young life. We are headed toward our little New Jersey beach town, which was the last place I saw my brother 37 years ago. We had walked the beach one night and he had given me solid brotherly advice about men. Then he left the next day and he was gone. In the years before that, though, he had taught me to windsurf, and before that, to ski. Once he had hauled his drums up from the basement and put them next to the piano, and we scratched out a halting version of "Layla" together. I'm sure it was an assault on the ears. I'd love to hear it.

The Pat Metheny Group is playing "The Epic," and I'm experiencing that thing that happens when the beauty of the music itself sits alongside the pleasure of anticipating the notes. I start to wonder how many times I've listened to this piece over the decades, when suddenly I understand that this is what people mean when they speak about carrying our loved ones in our hearts.

In this moment my brother is alive, crossing time — again — to give me this song.

The tune plays on, exuberant and lush, loud and soft, fast and slow — all over the place. Our wheels keep turning, and I am overcome with joy. For the very first time, my memory of Greg is all blessing, free and clear.

WILD THING — I THINK I LOVE YOU.

It's tourist season in big sky country, which means the internet is lit up with tales of human-animal encounters that end poorly for man, beast or both. The details vary, but the common denominator is the ugly American deciding to get too close to something — bison are often involved — with tragic results.

The stories that make me the saddest are those in which the animal has to be euthanized. The best I can muster for the human instigator is emotional neutrality, which is a step better, I guess, than the derision they generally earn from internet commenters and wildlife professionals.

Boundaries. We are a species with boundary issues.

This is on my mind at the moment because a little gray squirrel who started coming to our deck to raid the bird feeders has become my morning coffee klatsch friend. I call her Capt. Olivia Benson. She doesn't call me anything, but she does press her face to my window every morning for breakfast. Sometimes she crawls down from the roof and hangs on the screen. I'm sitting on the couch when this happens, so I turn around to see a demanding squirrel interrogating me with her stare — upside down. It will never not be funny.

When she started coming to the window, I'd grab some woodpecker mix, open the window, and place the seed on the deck railing. It was clear that while she was ready to bolt if I made any unexpected moves, she was betting on that not happening. She'd root through the seed for her favorite bits and I got to study her from just inches away. When she sat up on her haunches to chew, I could see she recently had been nursing. One nipple looked a bit abused, maybe a little infected. A mark on a rear leg suggested an injury that was mostly healed.

The day came when I decided to see how she would react if I offered seed from my palm. I didn't relish the possibility of being bitten, but I wasn't much afraid of it, either. I slowly stretched my arm out and opened my seed-filled hand. She approached, then retreated. Then approached again, and retreated. Four times. Then she carefully selected a peanut from the mix and stood up to chew.

Turns out she'll eat from my hand.

Within a few days, she grew comfortable enough to rest one paw on my fingers while she used the other to move the seed around, looking for a nut. Then she started placing both paws on my hand while she snuffled. Sometimes she goes for something that has dropped onto the railing, and her face brushes the side of my hand. These things are moments of heaven for me. I can't say why, it just has always been this way. Anytime I've been lucky enough to have a close encounter with something wild has been, for me, transcendent.

In addition to stories about Terrible People Getting Too Close to Wild Animals, the internet is alive with good advice on why wild animals should be left alone. Don't feed the ducks. Leave a newborn fawn alone; mom will show up. Put the baby bird back in its nest. If you find an injured animal, call a wildlife expert. Take down your hummingbird feeders at the right time so your little visitors get on with migrating. And for heaven's sake, don't take a selfie with a bison.

These are all good guidelines written for people who want to do the right thing but don't know what that is, as well as for those whose deepest consideration is whether they should post their dope video as a reel or a story.

And still. I want to honor wild animals and their right to stay wild while also honoring the human wish to connect, if just for a moment.

Decades ago, I was out for a morning walk when a hummingbird appeared right in front of my face and hovered there for a moment. It was astonishing. The bird seemed ... purposeful. Intentional. And yes, that's classic anthropomorphizing. Maybe the bird thought my nose looked like a flower and considered whether there was nectar to be had. No one knows. But on the rare occasion when we have a moment with something wild, some of us are filled with a sense of having touched with the divine.

It's essential to consider the ethics of how we behave with our fellow travelers in our wild, wild world. I think it's also important to acknowledge the unreasonable love so many of us have for these beings.

There are days when the best you can say about me is "Welp, at least she loves animals." And that's not all bad.

Every morning, after Capt. Benson has been breakfasting for a while, I put out a little more seed on the railing, then close the window and go about the business of being a human. She eats until she's ready to yield the railing to the mourning doves, then goes about her squirrel shenanigans. Scrambling for the trees. Clambering over rooftops. Chasing her mates. Living her best wild little life.

It's a thing to behold.

A FEW WORDS ABOUT LETTING GO

Here we are: summer.

Time for lighter clothes. Shorts, maybe. Shorter sleeves. Sleevelessness, even.

It is time for water. The pool. The lake. The ocean.

In which case, it is time for a bathing suit.

In which case, for many of us, it is time for the annual Festival of Self-Recrimination.

We'll wiggle into the suit. Adjust the parts. Take a side eye view at the mirror. And for many of us, we will then bathe in bad feelings.

But this is not mandatory. It's just a bad habit.

So this year, I am going to change it up. I'm going to insist on giving myself permission to release my grip on all that, because:

I have a body, yay!

I have a bathing suit, yay!

If I am lucky enough to be near the water, then I'd better be smart enough to stop gazing at my middle-aged navel and look outward. At light glistening on the waves.

At a few small clouds kissing the blue.

At a natural world insisting on being perfect. In spite of us. In in spite of it all.

HELLO. THANK YOU. I LOVE YOU. SO LONG.

The first of the iris blossoms are on the retreat. I still see tight buds waiting to open, but not as many as a week ago. In the blink of an eye, the festival of purple in our front yard will be gone for another year.

Will I be a little wistful? Heck, yeah. Give me my melancholic minute, won't you?

This marks our third iris-blooming season since we moved into our new house. The first year, the flowers awoke while we were still unpacking boxes, and the show was a spectacular welcome. I felt unearned pride by their presence. We are not gardeners, just people who try to stay reasonably on top of the weeds and buy a few pots of flowers in summer. But look, neighbors. OUR IRISES!

Yet we didn't earn them. They were a gift, planted years before by the couple who built and owned this home for its whole life before we came along. They're both gone now; their kids put the house on the market. But I think of the Stanfords from time to time, and imagine who they were and what their lives were like when our home was still theirs. I silently thank them for the nice wood floors and the bay window.

And in spring, when the iris buds become a festival of dancers in swirling dresses, I thank them again, with emphasis.

Not long ago I was at dinner with good friends, talking about work, love, the pandemic, and understanding what is and isn't important as we occupy what writer Arthur C. Brooks (generously) calls "the second half of life."

Almost in passing, one of my friends observed, "This is all we have, right?" She drew a circle around the table with an index finger. "Just moments, like this."

Moments like this, meaning: beautiful and fleeting. Not to be wasted. And of course, my friend is right. We are all old enough to have learned that the most gorgeous moments and feelings and experiences that light up a world — the ones we most want to save for later — are just like all the other moments, in that they refuse to last forever.

Hello.

I love you.

Thank you.

So long.

When I grow up, I want to be a lady who spends as little time as possible on feeling wistful about the passing of the iris blossoms. I want to revel in their budding and unfurling, and their ecstatic dances in the sunlight. Then, when they're gone, to be happy for having witnessed their outrageous beauty.

A Few Short Paragraphs About Hope

Artificial intelligence is everywhere these days — in art, in conversation, in journalism, and even in the halls of Congress. Seems we've never seen cultural disruption like we're about to see with AI, which leads me back, as so many things do, to Sting. Specifically, to these lines from "If Ever I Lose My Faith in You" from the quaint 1990s:

I never saw no miracle of science/

That didn't go from a blessing to a curse

So add AI to the list of factors that seem poised to annihilate life as we know it. You have to wonder, is there any hope? Is hope even worth having?

Ted Lasso would have something nice to say on the matter. In the meantime, I guess it's up to every individual to answer. Some of us have to think harder than others. After a serious bit of cogitation, what I decided was that hope makes little sense, but hopelessness makes none.

We need hope. It's not the last bus out of a godforsaken town, but it is the gas in the bus.

Metaphor switcheroo: We can't just wish for hope, we have to cultivate it through action. I hate this part; I'm lazy and I kill mere houseplants. But having hope these days seems to depend not JUST on our willingness to plant literal flower bulbs as the weather turns harsh — although such common expressions of optimism remain essential at the soul level. It's also about taking one or two regular actions, big or small, in the general direction of saving the world.

In spite of it all, we must assume we'll live to retire and save for retirement. And we write letters to people with power. We must assume our kids will have a future that will require them to hold jobs, and we send them to college. And we run for office. Or march, if that's our jam. Or write letters. If we happen to have actual high-level training, we apply it to taking down Godzilla.

And we train for a 10k or learn another language or buy more books or whatever else brings joy to the day.

We don't do ALL the things, because we're already exhausted. But we pick a few meaningful actions for ourselves and one or two on behalf society in general, and in that way we keep our own personal hope feedback loop running.

Hope is not always rewarded, but it outperforms hopelessness every time.

By the way, as it turns out, Ted does have something to say on the matter, season 1 episode 10. "It's the hope that kills you. Y'all know that? I disagree, you know? I think it's the lack of hope that comes and gets you. See, I believe in hope."

Me too, Ted.

Oh, hey, thanks

As we begin the time of giving thanks, it seems only right to mention my dog's butt. It's golden, round and fluffy, and, for reasons we'll never know, it is crowned by a mere niblet of tail, which flutters like a hummingbird when she's happy.

My dog's butt is my second favorite butt on the planet, and I am deliriously grateful for it on a daily basis. Well, and the rest of her. If you are having a hard time mustering a sense of thankfulness, I recommend reaching out to a dog and seeing where that takes you.

I am also thankful for Costco.

I used to think Costco was some kind of torture chamber designed specifically to terrorize those of us who are easily overwhelmed in large, windowless places filled with people who have no physical sense of self-awareness. And it is. But, well — the rotisserie chicken and the supersized containers of Greek yogurt. Color me grateful.

On any given day, I spend a solid 15 minutes fretting about the long list of improvements or upgrades our little house needs, yet still — our home is perfect. Warm and right-sized and wildly luxurious in its very modesty.

I am grateful for the sweet sound of my husband's voice speaking tenderly to the dog when he doesn't know I can hear him.

And for the joyful early hours of a Saturday morning, when an entire unencumbered day stretches out before me.

And for journalism and art: I love those worlds for my personal experiences with them, and more generally for what journalists and artists give us every day.

And I love Advil.

One of my brothers asked me recently if I ever think of moving somewhere else after retirement. Truthfully, boringly, unadventurously, I said no. I've lived in or around this city of thousand punchlines since I was 5, and feel connected to it in a thousand and seventeen ways. Not everyone enjoys a sense of being well rooted in community, but I feel that way about Cleveland. I'd trade it for a beach house on the Atlantic, but not much else. I am so grateful for this city — as a reasonably metropolitan place situated alongside a big lake, and as a network of humans connected by innumerable micro communities. It feels like a deep blessing.

As does the sensation of a sharp pencil tip across good paper.

As does coffee.

And my elder daughter's sense of humor, and my younger daughter's weird and occasionally annoying ESP, and the astonishing wisdom they both have had for nearly all their lives. I count my kids among my friends, who are more numerous than I could have imagined as a wallflowery high schooler, and also more funny, smart, kind and generous than I deserve.

Other undeserved gifts: Fresh peaches.

Cheese.

The memory of shopping with my mom.

Good pay and engaging work at a place that performs medical miracles.

Books and books and books, and many ways to read them.

The hawk on the deck and the squirrel at my window.

When I was growing up, we had bountiful Thanksgiving dinners, but I don't remember us ever talking about what we were grateful for. This might well be a failure of my Swiss cheese memory, or it could be that people spoke a lot less about gratitude then. In any case, when I had my own family, and we started going around the Thanksgiving table to say what we were grateful for, I felt like I'd invented something. Turns out much of the world was already on the gratitude train. I had just been late, as usual.

Well, better later than never. It really is true that when we stop to name a few things for which to be grateful, they start to multiply. This is an especially meaningful effort in times when we are drowning in images of others who seem to have more of everything.

Envy and bitterness can be pretty tempting until I'm reminded of the gifts I wake up to every morning. I am living amid an embarrassment of riches.

So thank you for the pair of jeans that actual fits, and for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and the sun making shadow art on my walls. And thanks for your own fine eyeballs if you've read to the end. I'm grateful for you, too.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Church on Tuesday

When it comes to churchgoing, I've been better at concept than practice. During my childhood as a member of a Mass-going family of Catholics, I experienced four emotions every Sunday.

1. Excruciating boredom.

2. Lucy-and-the-football despair each time a priest failed to deliver the juicy homilies I allowed myself to long for — the ones that might illuminate the magical God mysteries and their relevance to my life.

3. Anger about all the kneeling, for crying. Out. Loud.

4. Deep certainty that I was surrounded by people who grasped things I couldn't. I did not know what to do during silent prayer. I didn't know how to not feel like a faker reciting the Apostle's Creed. In fact, the more I said any of the refrains or prayers out loud, or sang the pious songs, the more I felt like a liar. Not because I didn't want to believe, but because I needed to work things out first organically. I had to get there honestly.

Today I am a VERY sporadic visitor at Protestant services, but on my rare visits, I now know why I'm there: to connect with others stumbling in a spiritual direction, to hear about Jesus, who gave us a pretty good blueprint for living, and — this is key — to wake up my better side: the kinder, more reverent, more outward-focused, patient person; the radically non-judgmental friend, the generous stranger, and a lady who tries really hard to be better about returning messages.

I do not dress up for church, but I definitely bring a Sunday Best attitude of reverence, gratitude, softness and integrity. That's the same spirit I wear for a walk in the woods, by the way. Walks in the woods happen far oftener than visits to church, but they have almost everything in common, except that the birds and bullfrogs do the singing. That works out better for everyone.

Walks in the woods are church on Sunday. Absolutely they are. But what about church on Tuesday?

I had a moment of discomfort recently during a small conflict with some loved ones that really arose out of communication failure. To be clear, I had failed to communicate in a timely way about something of consequence. Naturally, the aforementioned loved ones were unhappy about this, and they let me know that. Not by yelling, just by ... saying so in a disappointed tone of voice. Which I interpreted as scolding.

I spent the immediate hours and days afterward wallowing in my persecution complex and assembling arguments for why I had not been technically WRONG and why they had been way overreacting. When I told the story to my husband, I went deep and wide with my woundedness. This was 21st century stubborn-as-a-rock opera. Listen to my aria, won't you?

So my question is, where was my church best on Tuesday? What happened to the higher, more reverent and spirit-aware version of me — the one who definitely shows up when summoned to church or the woods or for a good conversation with a friend? What can we do, those of us who believe in church spirit (if not so much religious hierarchies), to make sure we're wearing our Sunday Best on Tuesday, Wednesday and beyond?

My friend Celeste Glasgow Ribbins wrote a lovely book called The Power of Mustard Plant Faith. Celeste and her husband Mark, a Christian minister, are true churchgoers, but also human beings with the usual doubts and fears. In her book, Celeste uses that humanity to expand on the relevance of the parable of the mustard seed; how Jesus told his disciples that with faith the size of a mustard seed, they could move mountains.

Reading Celeste's book helps me. All I need on a Tuesday is a tiny, almost imperceptible moment of remembering the person who shows up at church or in the woods, with all the best thoughts and intentions and sense of connection to the universe. A mustard-seed moment of remembering can take the wind out of victim complex or self-righteousness. It can sometimes quiet me when I'm tempted to gossip, or give me a moment of pause that keeps me from being reactive. I imagine a time when it may even stop me from weaving yards of Irish lace out of threads of profanity while I'm driving, but that's probably down the road a bit.

A more religious person might set his or her sights on doing this because the Bible says we should, but as I mentioned at the top, I was raised Catholic, and The Church preferred that we plebes not try to read it on our own. Mission accomplished.

No, for me, church on Tuesday is about finding a higher self a little more often — say, daily — because it seems like the right thing to do. When I summon Church Karen or Walk in the Woods Karen, I feel like a better, calmer, less egocentric human being. That person is pretty good company. And that seems like reason enough.

On Being a Person Who Finishes Things

Years ago, a writer friend shared a draft of a book she was writing on a topic she was passionately interested in. She asked for feedback, and I gave her some, but the book seemed in good shape. Time went by, and occasionally I'd ask her how it was going, and she would report back on some improvement she was trying to make. The upshot, though, was that she was struggling to let it go and send her book to an agent or publisher. As long as she didn't, her project couldn't get liftoff. And from what I had seen, the book was in great shape, and the only thing blocking it was the author herself. I didn't understand it.

Boy, do I understand it now.

For a few years, I've been toiling away on a children's book tentatively titled "Hope Notices," about what happens when a curious, attentive girl goes to the beach hoping to see a whale. Now, this is a picture book, so every page is illustrated. For the purposes of finding a publisher for this kind of a book, all sketches need to be completed, and a couple of them need to be made into fully finished drawings. I'm only few sketches away from completing that process. I've also written, revised, workshopped, and re-revised the text. In other words, this critical first phase is almost done. But then again, that has been true for a while.

This is a time-consuming prospect in any case, but it absolutely does not have to be the drawn-out psychodrama that I have made of it.

Like my friend who couldn't quite get comfortable sending her book out for proposal, I, too, have been dilly-dallying for mysterious reasons. I make a little progress, then follow an impulse to create something else — something that my brain places in the "for fun" category rather than the "for work" category that a book project inevitably becomes part of.

I could hash through the reasons for all this nonsensical procrastination. Fear of failure? Always. Shiny object syndrome? Sure. Every new idea that pops into my head looks like something good to chase. Or maybe it's the deadline orientation built into me by a career in newspapers. This project doesn't have a deadline. No one cares if I set it aside for a bit.

It really doesn't matter, though.

A few years ago, I interviewed the author and illustrator of a critically acclaimed graphic novel and asked what advice she had for young artists. "Be a person who finishes things," she said. Her own book had been a 10-year journey. She thought it had taken too long. Yet she was proud that, 10 years or otherwise, she had completed it. And the point in being in a finisher is that not only do you have a completed project, but you establish yourself in your own mind—the most important place—as a person of integrity.

I really love my book. I love the character, the concept, the dog (of course!), the language, and the story. So I am going to give Hope the focus she deserves. I am going to be a person who finishes this thing I love and then carries it out into the world and hopes that someone else loves it, too — enough to share it far and wide.

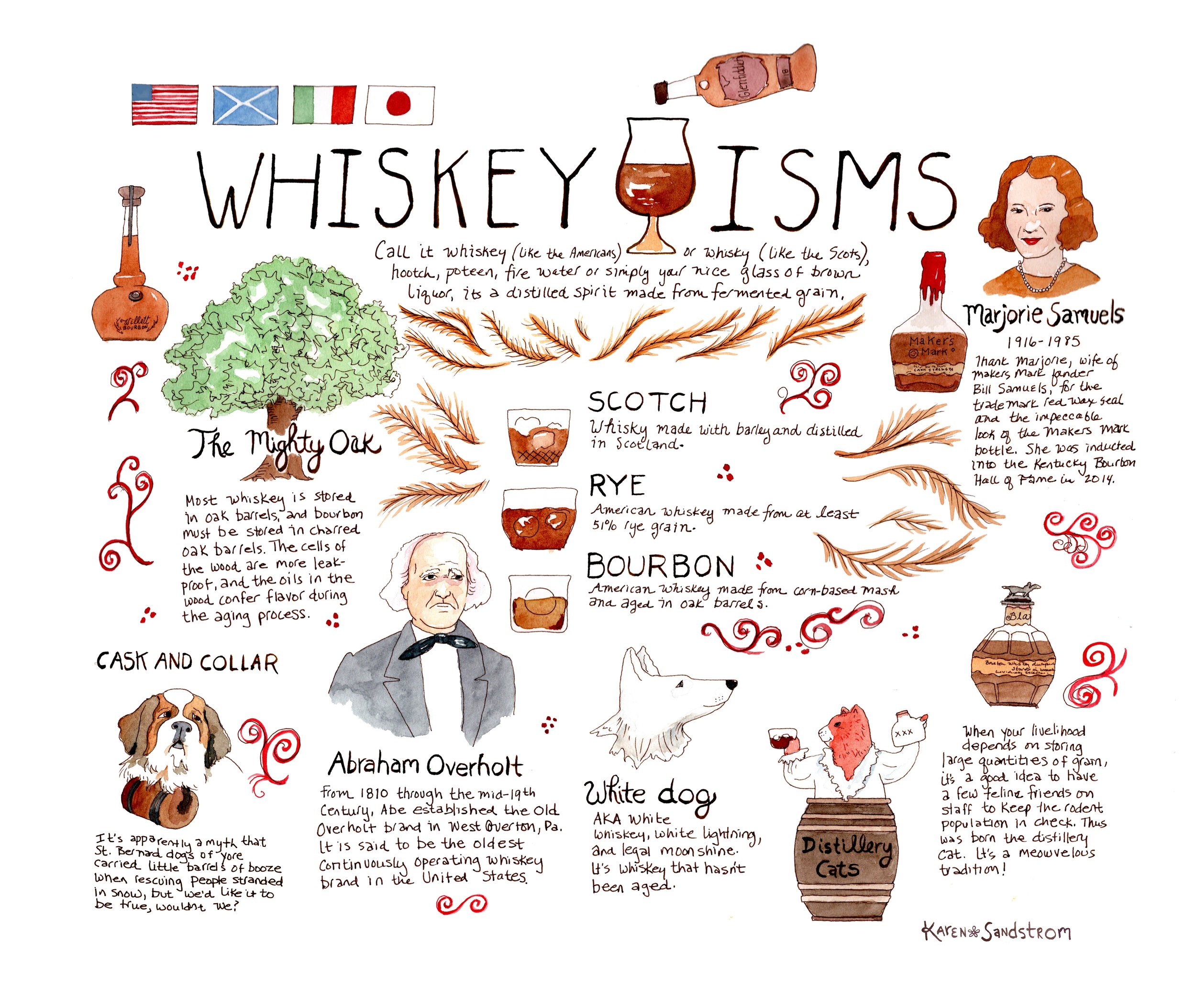

Our 0ld-Kentucky Roam

Early this year, when fate seemed determined to quash our family's traditional vacation week at the Jersey Shore, my husband and I decided on Door Number Two. We would spend a few days in the southern reaches of our home state, Ohio, then spend a couple more investigating bourbon distilleries in neighboring Kentucky.

Carlo was extremely eager to breathe the malt air. Over the years, he has joined the legions of aficionados supporting the American whiskey boom, as his burgeoning bar cart attests. Exploring the Kentucky bourbon trail had been on his list for a while, and neither of us had ever spent any real time in Cincinnati.

And me? While I suspected that any thirst for knowledge I might muster around the history of American whiskey could be quenched at the first distillery, I was nonetheless ready to give in to the adventure. My good-sport muscle needed some exercise.

So off to Cincinnati and Louisville we went in late June. The trip turned out to be, all at once, unremarkable and unforgettable, both better and worse than I had expected. This is almost always true. Even modest travel offers a tiny drama, a few joys and sometimes even a revelation.

These were some of mine.

I got reacquainted with the pleasures of the road.

City driving has killed all the affection I had as a teenager for getting behind the wheel, so it's easy to forget that I actually do love a good road trip: stretches of highway dotted by billboards and hay bales, stopping for road coffee at McDonald's, the sense of accomplishment in watching the odometer tick off the miles. For this adventure, I added "Carlo's Play List" to my iTunes library, and filled it with Rolling Stones, Talking Heads and Roxy Music. My eternally 17-year-old mind is still regularly blown away that we can just think of a song and then summon it into being. As Barry Manilow might say, "It's a miracle!" (Please note that I am NOT saying that Barry Manilow also is in my iTunes library. Although I am also not NOT saying that.)

The second worst moment turned out OK.

Sometime between our lovely dinner in Cincinnati's Over-the-Rhine neighborhood and planning a zoo visit, it became apparent that I had — ahem — poorly communicated, and that the person I thought was going to babysit Daisy was not, herself, actually planning to dog sit.

This was discovered by the person who had agreed to take Daisy during a brief interim period, then hand her off to the aforementioned unsuspecting dog sitter.

Confused? Never mind — both people were my offspring, who gracefully adjusted their lives and tag teamed on Daisy's care. But for an hour or two, I deeply considered that the only fair thing for the kids and the dog was to cancel the trip and drive back to Cleveland.

This plunged Carlo and me into a dark mid-afternoon of the soul. But my point in mentioning it is that anytime your brain whispers "There is only one path," remember a thing I learned in art school: There is always more than one solution. And there was. (Thanks, ladies.)

Organic culture is nice to find.

Let's be clear that, having visited three and a half distilleries, a giant alcohol retailer, Justins' House of Bourbon, and a couple of nice bars — including one where a drunk stranger plucked a cocktail cherry from his glass and insisted I eat it — I still know comparatively nothing about whiskey.

That said, it was a blast to pepper the New Riff distillery tour guide with my beginner's questions, and to finally understand what bourbon lovers mean when they talk about the "vanilla" and "spice" notes they taste in a given bottle. To be clear, my plebeian palette cannot actually detect those flavors, but at least now I know that they derive from the barrel-aging process rather than some guy in the back room adding flavor extract by dropper.

More importantly, it was a pleasure to explore deeply rooted Kentucky whiskey culture. Age-old families, farms and craft traditions that span a century and more. Recipes refined, passed down, kept secret. In a country littered with chain restaurants and bland shopping centers, it's a pleasure to see something distinctive and organic to its surroundings.

Whiskey tastes good.

I still can't much tell the difference between the brands, but I genuinely enjoy a snort.

The very worst moment might be one worth remembering.

I can't get around introducing a harsh note, so here goes.

We were traveling from Cincinnati to Louisville when the Supreme Court released its decision in the Dobbs case, overturning Roe v. Wade and introducing a new and terrible era in U.S. history. All that day, Carlo and I managed to remain in a vacation-y state of willful denial and relative good cheer. I bought a black T-shirt at Willett distillery that just says "Nope." (OK, maybe reality had begun to set in.) I gazed in wonder as a woman dipped the top of her newly purchased bottle of Maker's Mark into a vat to seal it with hot red wax. We dined in a restaurant at a beautiful old Louisville hotel, where the room was decorated by old whiskey bottles filled with flower petals. Across the room, a platinum blonde presented bodacious breasts only 30 percent contained by her dress; her date seemed pleased. It was hard not to look.

But that night, I laid awake simmering with a depth of rage and despair about our country that I have been unable to fully articulate. The next morning in our hotel room, exhausted, I started to weep and felt I would never stop. We were due to spend another day and night in Louisville, but I didn't want to see the Kentucky Derby museum. I didn't want more bourbon history, or a walking tour, or an art gallery. We agreed to leave after breakfast.

At breakfast in the beautiful hotel's dining room, a kind waitress took note of my blotched cheeks and damp eyes. With a voice filled with softness, she said hello, then asked, "How are you doing today?" Fearful of embarrassing myself with more tears, I merely nodded. The waitress turned to Carlo. "How are we doing?" she asked him. She seemed ready for however much or little either of us wanted to say. He told her we were OK, then she gently explained the breakfast buffet and pointed us toward the coffee. The whole encounter lasted about a minute, but it was so excruciatingly sweet and caring that I thought I would fall apart. Kindness can do that sometimes.

After we'd eaten, the waitress brought the bill. "Y'all didn't each much, so I just charged you for one," she said. Perhaps she thought we had just gotten some terrible, personal news — and in a way, that's what Dobbs has felt like.

But in the moment, I accepted her kindness as a gift of grace. I tried to tell myself that this, too, was America. I must remember her the next time I see someone who needs a body to ask them, "How are you doing today?"

Home rules.

One of the many luxuries we forfeited during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic was the pleasure of returning home after being away. Traveling never fails to remind me how much I love the luxury of suffering insomnia in my own bed. How lucky I am to have this particular roof over my addled head. How great it is to be reunited with the dog.

As my friend Becky often says, "Good to go, good to get home." And surely it was.

JUST LUCKY

A cardboard box has been delivered to your door. It's big enough to contain a full-size suitcase, but when you pick it up to take it inside, you find it light — almost as if it's empty. You grab a knife and slice the tape on the top, open the flaps and cast your eyes on a whole lot of Styrofoam packing peanuts. Eager to get to the treasure beneath the peanuts, you plunge your hands inside, sending a flurry of foamlets over the side. The peanuts are full of static electricity. They cling to your shirt, but you keep desperately pawing through the box. Peanuts fall to the floor and stick to the tops of your shoes. They grab the hairs on your arms, and hold like barnacles to your pants.

It's maddening.

You brush at them, but manage only to transfer them to another part of your body. You sigh, and go back to searching, only to get to the bottom and realize the box never had treasure, only packing peanuts, which are now everywhere — on your clothes, on your skin, on the furniture. And they are a bitch to corral because, well ... static. Getting all those peanuts back in the box is POSSIBLE, but it's really difficult. Every time you think you've gotten them all back in, you find one stuck to your hip or your hair or the dog's tail.

This, I've decided, is exactly what it's like to indulge in worrying about aging. To open that box is to be attacked by staticky thoughts that resist being put away. We pick them off, but they just cling to something else.

Are we "old" yet? Maybe we're older but not, you know, "elderly."

Wait, when does elderly begin?

Are we too old to ride a motorcycle? To wear big earrings?

How old do our younger colleagues think we are?

Have we become the old person in the group and we don't even know it?

We always wanted to learn to play piano, but at this age, what's the point, right?

Years ago, a friend made a joke about how one day he'd start to have the "old man smell" and not even know it. I laughed, but I also thought, "Do old men smell weird? Do old WOMEN smell weird? Am I destined to acquire the old woman smell? Maybe I already smell like an old woman and this is his way of letting me know."

You see what I'm saying, right? Age-fretting is the cardboard box filled with nothing but stupid peanuts, and it's best to resist opening it. There is no treasure inside the worry box. We simply burn the very resource we are most worried about losing.

When I was a 47-year-old pursuing a bachelor's degree in illustration at an art school filled mostly with people born in the 1990s, I fried thousands of brain cells worrying about my age. I obsessed about how age hindered me. How it would prevent me from achieving goals. How perhaps the loss of cognitive elasticity was making me extra-dense and hard to teach. Every struggle or failure was harder than it needed to be, because I had a chorus of terrible devils in my ear, blaming it all on my geriatric situation. Which was, of course, ridiculous. Sometimes we just agelessly fail.

A few of my professors seemed to have sized me up as a self-indulgent housewife, and I got fixated on that for a while before deciding it probably didn't matter.

On the other hand, though — and this is important — I was doing art school. Even though I was pushing 50, I did not think it was weird or wasteful. Inside, I was still me, and that person wanted to be better at making art.

School was exhilarating and rewarding. At times, it was also deeply humiliating to be less skilled than a bunch of 18-year-olds. But not having studied art at 18, doing it now seemed like the next best decision. Much smarter than not doing it at all.

And it was. It was the best. One of the best things I have ever done.

And of course now 10 years have passed, so I see how very young I was at the time.

There's probably a fine line between fretting about age and occasionally partaking in meaningful reflection about our own mortality — taking stock as we move forward on the great conveyor belt of time. I think that's a line worth considering, but you know — not obsessing over.

But by now, most of us have friends or family members who never got the chance to worry about being too old. If they were here, they'd tell us we're lucky. They'd probably suggest we get out of our heads for a while and get on a motorcycle or take up piano or bake a cheesecake or call some friends.

And that's what we should do. Every time we see the box on the porch, we should shove it to the side and carpe the dang diem.

THE KIDS ARE NOT ALRIGHT—BUT THEY WILL BE

On Monday night, I watched a Zoom presentation by a handful of high school student leaders involved with Sandy Hook Promise, the nonprofit that grew out of the 2012 murder of 26 people, most of them 6- and 7-year-olds, at an elementary school in Newtown, Connecticut. They wore green Sandy Hook Promise T-shirts, and they calmly and confidently explained what they do in their schools to begin to tackle the problem of school gun violence.

They create campaigns to encourage the student body to notice and report when something seems not quite right with a classmate.

They engage teachers and others to commit to being "safe adults"—people with whom they can share their concerns.

They do things as simple as wearing nametags to encourage friendliness, and to make it easier for everyone in their school to strike up conversations. They work to flip clique culture and stigmatize (my word, not theirs) the kind of routine bullying and insiderism that have been part of high schools since high schools were born.

They are advocates for gun safety. They do not seem at all naive about the political challenges of changing policy.

As members of a generation that has grown up participating in active shooter drills at the start of each school year, these high schoolers are poised and friendly as they explain what they want from grownups. Sure, they want us to use our votes well, but they also just seem to really want to be heard. Not because they are snowflakes who need their feelings coddled, but the opposite: they have expertise that a 50-year-old doesn't have.

They want forums where they can speak from the wisdom that arises from facing a problem they did not create but know they have to help fix.

Strategic. Matter-of-fact. Solutions oriented. Non-hysterical. Mission driven. This was my impression of these students after listening to them for a while.

Frankly, it was a relief to hear them. I have been so bound up in fury at my generation for allowing this infection of gun violence to flourish—so bummed out by our self-made Chinese handcuffs, where every movement on the solutions side causes tightening and intractability on the other—that I had fallen into a trap. It's our job to fix this; we will never fix this.

That has been my thinking.

But what if help is already on the way? What if, between filling out college applications and going to prom, between music lessons and winning home games, the cavalry—battle-trained by a culture that, frankly, today's parents and grandparents never lived—the kids are already suited up, utterly done with our failure of imagination, and committed to upending the status quo?

I think they are. I think they know what they're up against, but they also know what they're doing, how much work it will take, that the solution will be many pronged and that it will require steely resolve and endurance.

When these kids were infants, we promised they would be in safe hands. We failed. The young people I heard speak seem utterly unwilling to watch helplessly from the sidelines to allow that failure to repeat itself. So yes, shame on us. And good on them.

Watching and listening was almost rejuvenating. For the first time in a while, the sun passed in front of the moon and blotted out the darkness. I glimpsed what it might be like to go from impotent despair to absolute determination to destroy the virus of gun violence.

The cavalry is coming. I wish it had been us, but either way—it's coming.

Reclaiming the Bold

It's a sunny day in the 1980s, just before I start my first real job writing for a newspaper. Mom and I are shopping at Baltimore's Inner Harbor, and we are with her great friend Marguerite "Wiggie" Hyman. Both Wiggie and her husband Alan were kind and beautiful, but Wig had the big personality: husky laugh, statement jewelry, curious mind.

Wig and my mom — no slouch herself in the style department — are helping me start a wardrobe befitting my first real job. Well, they are helping me buy what they imagine a lady reporter should wear, which will turn out to bear no resemblance to the way underpaid young journalists actually dress for a day at a failing newspaper in Painesville, Ohio. But for now we are at an elegant shoe store, and Wiggie picks up a sassy low-heeled pump made of matte red leather.

"Everyone needs a pair of red shoes," Wig declares. "People think red won't go with anything, but it's not true. You treat red like a neutral. It goes with anything."

A clerk conjures a pair in my size, and when I slip into them, it's magic. I am in Dorothy's ruby slippers, instantly more powerful. Magnificent.

To this day, I believe in the transformative power of red shoes. I also believe in Wiggie's bold, red-shoe spirit, even if summoning it requires more effort and intention than it seemed to for her. My version of "bold" is Wiggie Lite — more internal attitude than outward expression — but it serves me well, when I remember to use it.

It has dawned on me recently that I haven't worn red shoes in a while, literally or metaphorically. I mostly blame covid. Two years of watching variants and working at home in bare feet has somehow made me simultaneously fatter and smaller. Timidity has crept in. What with all the worrying, wondering, frustration and fear, all that searching for silver linings in the covid cloud, I forgot boldness was even a thing.

That spirit totally slipped my mind.

Maybe this feels familiar to you. Everyone's pandemic experience has been a little different, but it's fair to say the lockdowns and vigilance that helped keep us above ground generally ran counter to living large. And it's too bad, because a pinch of bold makes everything better.

Bold amplifies love. It isn't the same as fearlessness, but it can turbo-charge courage. It is not heedless or careless or willfully ignorant — it absolutely can coexist with masks and vaccines, for instance — but it prefers that we don't overthink. Bold sometimes shows up for decisions we later regret. (Admire my impressive restraint in not mentioning ear gauges, won't you?) No problem. Mistakes will be made, and boldness requires radical acceptance of the existence of risk.

It also often accompanies wisdom, brilliance and demonstrations of grit.

Embodying boldness is not about being loud or garish, although I just saw a video clip of seventysomething Elton John wearing a conflagration of beads and sequins and thought, "Now THAT is bold." And it was, because even Sir Elton, with his history of Liberace chic, still must summon decisiveness, confidence and action to slip into the sartorial equivalent of a Vegas Christmas tree.

Decision + confident action = bold.

It's red shoes, and it's an introvert starting party conversation. Bold is our friend Eric, who recently trained for and landed a job in a brand new field. He's 78. Bold is asking someone to explain something better and swallowing the urge to apologize for yourself when you do it. It's checking your rearview, then stepping on the gas to merge onto the highway and deciding you will be just fine.

I could go on. Could you? What's the boldest you've ever been? What's the next bold thing you'd like to do? If it takes a minute to think of anything, I understand — same here. It's worth considering, though.

Even for those of us least scathed by covid, the pandemic has been a thief, and it might be time to start stealing back some of the parts of ourselves we've been missing. Those of us mourning previous states of self-assurance might literally start by buying red shoes, and I'm not ruling it out, but heck. I still work in bare feet. How often would I wear red shoes? Where would I go?

Yet that's the point. I am tired of tentative. I want to stretch out and reconnect with my bolder self. She had fun, that one. I'm thinking about where to wander, what to see, and how to bring red-shoe spirit to every kind of travel, even if it's just to walk the dog.

Although to be clear, I want to do more than walk the dog.

Chin up, eyes ahead. I intend to reclaim the long stride.

You can come along if you like.

Why to Love a Cairn

If you want to squabble over something other than politics on social media, post a picture of a cairn.

You know what that is, right?

A cairn is a decorative little tower of rocks and pebbles that some people like to make when they walk on a beach or hike through the woods. Cairns are usually small, but if you come across one, the fact that it was made by the human hand will be unmistakable. At our old house, one of our neighbors had an ever-changing sculpture garden of cairns in her front yard. If they signified something, I never knew what, but I loved strolling by and admiring them. Which is part of why I was so surprised to find out how deeply some people hate a good cairn.

Years ago I came across a thread blazing with fury under a photo of a cairn that one of the park systems posted on its Facebook page. A few of the haters attempted to justify their anger by invoking the environmental impact of cairns — something about disturbing insect habitat. Really? Many interactions with insects over the years tell me that the bugs abide, dude.

No, the anger wasn't really about the bugs. A cairn is a Rorschach test, and when cairn haters come across one, what they see is an egregious display of human ego. They imagine a person who, surrounded by nature's gifts, has to declare, "I was here." A shocking number of people on that Facebook thread said as much, and they described the glee they felt at kicking down a cairn for just that reason — to erase the signature.

Me, I love cairns. I thought about them last weekend, when I visited the arboretum to take in the beauty of prepubescent spring. The daffodils had awakened, and the ornamental trees had started to think seriously about bursting. A wood frog chorus rose and fell, rose and fell. Chatty cardinals and red-winged blackbirds sang to their friends. At one point, as I was sitting on a bench drawing a tree in my sketchbook, sunlight kissing a gentle rise in the land in the background, all I could think was how happy I was to be surrounded by nature. And then I remembered: This nature is mitigated by human effort. I can be here only because others protect and nurture these acres and then invite me in to appreciate it.

And then I was happier still.

It is so easy to notice the opposite — the ways that people injure the planet. Right now I am assembling a list of examples of humanity's ill treatment of Earth, but you don't need them, do you? To bear reverence for the miracle of nature is to keep a sad accounting of its desecration. Noticing is truly the least we can do.

But if we're not careful, noticing the harm becomes a habit that crowds out the other stories — boundless examples of people putting their reverence for nature to work by interacting with it for the good.